Suma – all names are pseudonyms – worked at a free health clinic and in an interview, she spoke about the free health services the clinic offered to people who live below or on the poverty level. Suma emphasized the importance of offering free services to help people like Rachel. During a routine screening at the free clinic, Rachel was diagnosed with early-stage uterine cancer. The oncologist who volunteered her services at the free clinic referred Rachel to a large hospital to receive treatment. However, the hospital refused to see Rachel because she was uninsured and too poor to afford healthcare privately. Suma explained that the free clinic’s nurse case manager spent hours on the phone advocating on Rachel’s behalf. Rachel is not alone in struggling to pay for care: more than 14 million people have acquired an estimated $220 billion in medical debt. Approximately four in ten adults in the United States have medical debt, with uninsured individuals, parents, people with lower incomes, Black and Hispanic adults, and women being disproportionately affected. Only when the free clinic promised to foot the bill was the nurse able to get Rachel the appointment she needed. However, as we found out through our research on medical debt and uncovered healthcare costs, Rachel was one of the few people who could access such a resource because financial assistance for healthcare is difficult to find and apply for.

We learned about people’s struggles to access and pay for care through our research on medical debt in the United States. In the autumn of 2024, a group of 18 undergraduate and graduate students and one professor conducted seven semi-structured interviews with three healthcare workers whose patients may struggle to afford healthcare, and four representatives from non-profit organizations and a hospital, who assist people who have incurred medical debt. In the interviews, we asked people about their work, the challenges they encounter, and their recommendations for improving access to financial aid. We held these interviews over Zoom and transcribed and analyzed them using the qualitative analysis software Dedoose. The interviews are part of a multi-year qualitative study and recurring anthropology course on qualitative research methods that investigates the wealth and health ramifications of uncovered healthcare costs in the United States. Our research aims to understand what people do when they incur uncovered healthcare costs. We focus on people who have, or have had medical debt, and on organizations, groups, and individuals who help people navigate or stave off financial ruin. In this essay, we use the interviews conducted in the autumn of 2024 to demonstrate that hospitals and clinics with financial aid systems fail many of the people they legally are meant to serve—ultimately worsening people’s struggles to pay for healthcare.

The United States is unlike other well-resourced countries, which provide their citizens with affordable quality healthcare. In contrast, the United States has a multi-payer health system with widely different health insurance plans for different groups, each with their own eligibility criteria, enrollment conditions, service delivery, billing and payment structures, prescription gaps, and medication coverage. The country does not have a centralized agency that negotiates service delivery or prices and the health system’s fragmented and decentralized nature makes access to healthcare difficult and unequal, with the greatest health disparities experienced by people of color. Excluded from care or unable to afford it, people must devise various strategies to meet their health needs, including mobilizing social networks, borrowing money from friends and family, stockpiling samples, and using street entrepreneurs to obtain the medication or medical supplies they need. The 2010 Patient Protection Affordable Care Act expanded access to health insurance coverage for millions of people. However, the 2010 health reform remains contentious as elected officials disagree on the need and degree of subsidized healthcare. Rachel is one of the many people who get caught in the country’s expansive, expensive, and fragmented health system, which offered her few opportunities to access affordable life-saving care.

Recognizing the financial and emotional toll that uncovered health care costs have on people, federal and state governments have sought to curb medical debt. The U.S federal government passed the “No Surprises Act” to protect people with health insurance coverage from receiving “surprise medical bills,” which include bills provided by out-of-network providers working at in-network facilities. The Act seeks to protect patients from being responsible or liable for higher amounts than the in-network price of the service received. Several states have implemented new consumer protection laws that set minimal standards for hospital financial aid programs, improve aid application processes, and restrict certain debt collection processes. While these legal initiatives may protect some patients from receiving unexpected medical bills and help patients manage healthcare costs, they do not eliminate costs as a structural barrier to accessing and receiving high-value, affordable care. These initiatives do also not challenge the implicit moral toxicity prevalent in the United States that every person is responsible for their health and wealth, and they do not address the social and economic inequalities that limit people’s options to take care of themselves. Our research shows that healthcare institutions mandated by law to provide financial assistance intentionally make it difficult for people to use the resources that counteract high medical costs, obscuring the fact that Rachel’s struggle to afford care was not a personal flaw but a structural problem.

First, many hospitals that are mandated by law to provide financial aid to cover health services do not actively help patients access the financial assistance for which they are eligible. Hospitals that are exempt from paying federal income tax (including but not limited to governmental, public, and non-profit and for-profit hospitals) are required by law to provide benefits to the community, which can include the provision of free or discounted healthcare services under a hospital’s Financial Assistance Policy (FAP). Hospitals should “widely publicize” their written FAPs and describe the hospital’s eligibility criteria, assistance levels, and application process. However, federal law does not specify what widely publicized means, generating much difference in patients’ ability to know about a hospital’s financial aid policy. Moreover, hospitals are allowed to set their own assistance levels, spending limits, and service delivery, and they use widely different eligibility criteria to assess a person’s “worthiness” of financial aid, such as income levels, personal assets, residency requirements, and determinations of emergent or non-elective service delivery. For instance, income level criteria across hospitals range from 41 to 600 percent of the federal poverty guideline. Moreover, financial aid requirements also vary greatly across states and federal oversight and enforcement is weak, adding to patients’ barriers to access, apply for, and use financial aid for health services.

Even when patients are able to successfully apply for financial assistance, big loopholes in the system may still saddle them with large medical bills because, for example, healthcare providers working as independent contractors are not bound by their hospital’s financial assistance policy and can, and will, bill their patients separately. One of our interviewees stated that, “[Financial aid documents] are not easy to use, they are not publicized, and [hospitals] may resort to aggressive collection strategies to collect patient bills.” This interviewee highlighted not only the inaccessibility of financial aid resources but also the fact that many tax-exempt hospitals have taken Extraordinary Collection Actions (ECAs) against patients with medical debt, such as reporting outstanding bills to credit rating agencies, suing patients, or selling the debt to commercial debt collectors. If tax-exempt hospitals would actively help patients access financial aid resources at the time of their visit or at the time of payment, fewer patients would end up in unnecessary financial or legal distress.

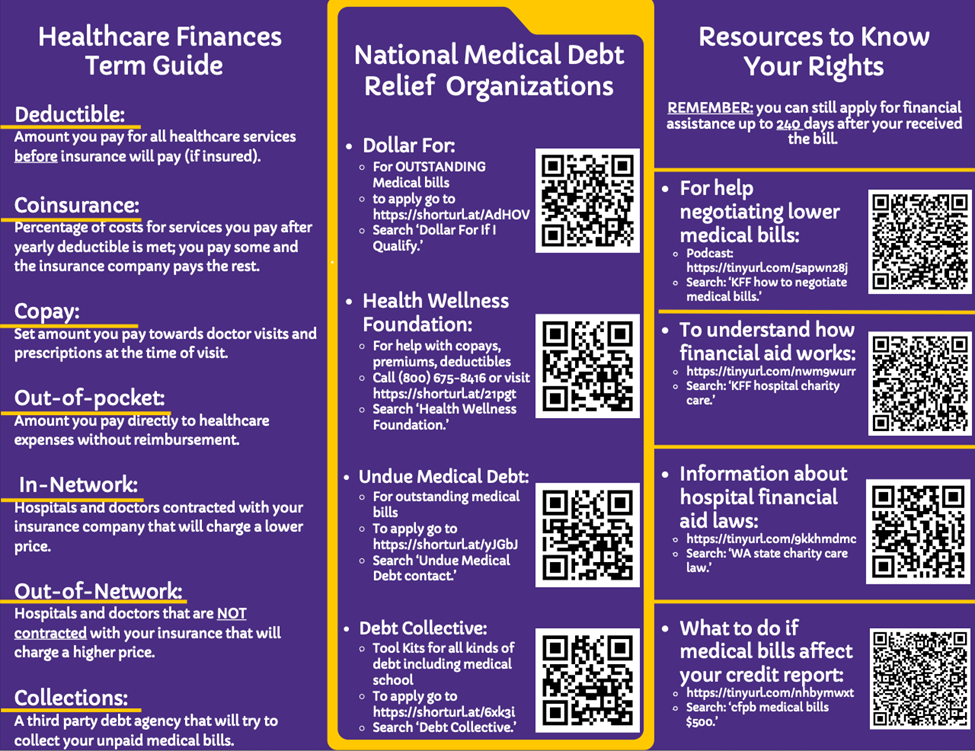

Second, financial aid documents are difficult to read and understand, which increases people’s struggles to use financial aid to pay for healthcare. Strengthening patients’ financial and health insurance literacy can improve their insurance knowledge and financial skills and reduce financial hardship. While greater financial literacy can help patients better manage their care and costs, the complex financial policies and insurance language require more than understanding basic financial principles. Financial aid policies are often filled with complex terminology and financial jargon, and they lack consistency across health facilities. For example, the University of Washington Medical Center’s financial aid policy describes their eligibility criteria as “[m]edically necessary health care rendered to indigent persons when third-party coverage, if any, has been exhausted, to the extent that the persons are unable to pay for the care or to pay deductibles or coinsurance amounts required by a third-party payer based on the criteria in this policy.” This policy fails to communicate the details of eligibility, and who or what is responsible for which part of which healthcare bill. Financial aid documents’ ambiguity leads many individuals who could qualify for financial assistance to be less likely or unable to apply, thus leaving them at great risk of being saddled with steep medical bills they cannot cover. A social worker we interviewed explained that financial aid assistance is “a system designed to confuse people.” The social worker emphasized that the obscurity of financial aid policies and health insurance structures is intentional, making it difficult for patients to use available resources that can decrease their financial burden when needing healthcare.

Third, medical schools fail to educate future providers on health policy, despite medical students’ interests in understanding the complexity of the US health system. Hospitals, in turn, add to the lack of understanding by not providing their providers with the knowledge of the financial aid policies available. In an interview, a pediatrician at a large hospital system shared that if a patient’s family asked about financial assistance, all she could do was refer them to the hospital’s billing department, as she was never informed about the hospitals’ financial aid resources. She also mentioned that every state and healthcare system she had practiced in had different eligibility requirements and resources, which created even more confusion and made it more difficult to help her patients financially. This pediatrician is not alone in lacking the knowledge and resources to communicate with patients about costs. Oncologists, among other providers, have reported a discomfort discussing financial resources with patients, a lack of insurance and financial knowledge, insufficient training, and wanting to provide standard treatment irrespective of patient insurance or ability to pay. Hospitals and clinics fail to equip their providers with the techniques, confidence, and knowledge to help patients access available financial aid resources, leaving an important patient-centered avenue of assistance underutilized.

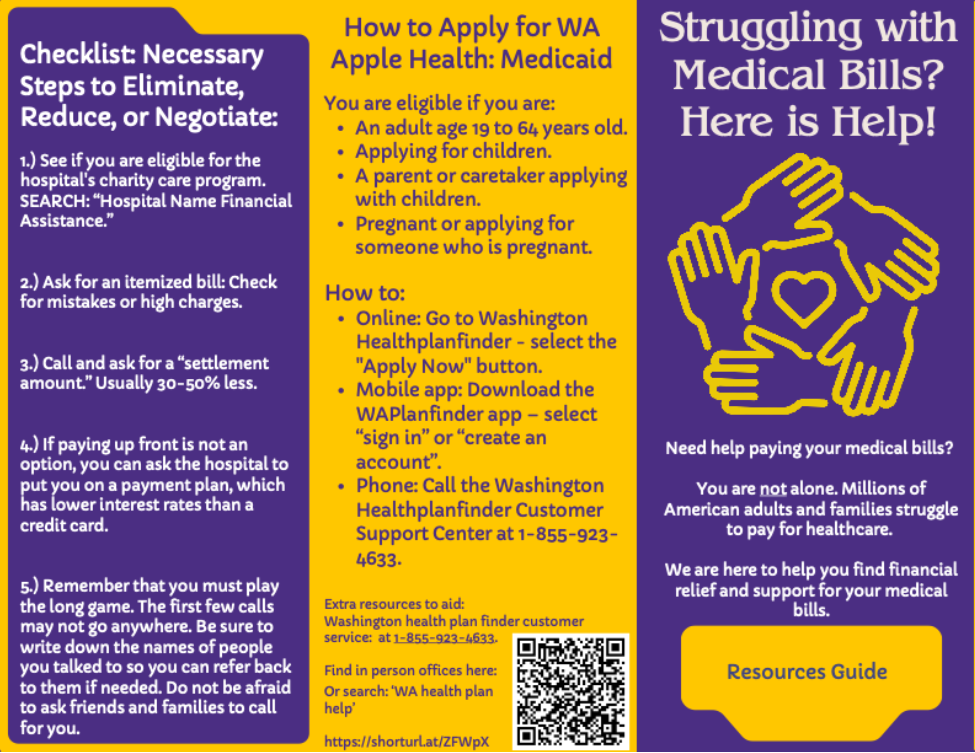

In summary, our research challenges the notion that incurring medical debt is a personal issue and posits instead that people’s struggle to afford healthcare and access financial aid is an institutional barrier that require systemic solutions. Hospitals that are legally mandated to offer financial aid fail to help patients from accessing the resources that could help them cover their healthcare costs. Financial aid policies are often ambiguous, leaving patients unaware of available financial assistance, unable to determine their eligibility, and potentially burdened with exorbitantly high medical bills. We do not dispute that it is essential that patients are equipped with the tools to understand financial assistance documents, but policies should also hold tax-exempt hospitals accountable for ensuring that patients know about, enroll in, and use the financial aid policies for which they qualify. Our interviewees emphasized that education for both patients and providers could play a significant role in improving access to health care services and resources and reduce the onset of medical debt. A health financial literacy curriculum should be mandatory for all healthcare staff to ensure they can best serve their patients’ needs. The distribution of user-friendly financial aid guides in clinical settings, such as the Medical Debt Guide below, could help more patients understand what they can qualify for, what their rights are, and how to advocate for themselves when needed. Addressing patients’ struggles to afford and access healthcare as an institutional and systemic issue instead of as an individual problem helps create a more equitable and accessible health system that enables patients like Rachel to prioritize their well-being over having to manage their medical debt.

Marieke S. van Eijk, Ph.D. is an Associate Teaching Professor in Medical Anthropology at the University of Washington and the Principal Investigator of the multi-year qualitative research study on medical debt in the United States.

Addie Behrens is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Psychology and Medical Anthropology at the University of Washington.

Alyssa Sabaruddin is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Earth and Space Sciences with a minor in Anthropology at the University of Washington.

Rylie Sapp is an undergraduate student double-majoring in Public Health and in Medical Anthropology and Global Health at the University of Washington

Nadine Urvater is an undergraduate student studying Medical Anthropology and Global Health at the University of Washington.

Students in the Qualitative Research Methods course created this guide to help individuals and their communities navigate medical debt.